Back in November, I shared some thoughts about teaching listening at the TESOL Regional Event in Madrid. Here, I’ve reworked those thoughts into a blog post that talks about a) why listening is so tricky to teach and b) some activities we can use to help teach listening more effectively.

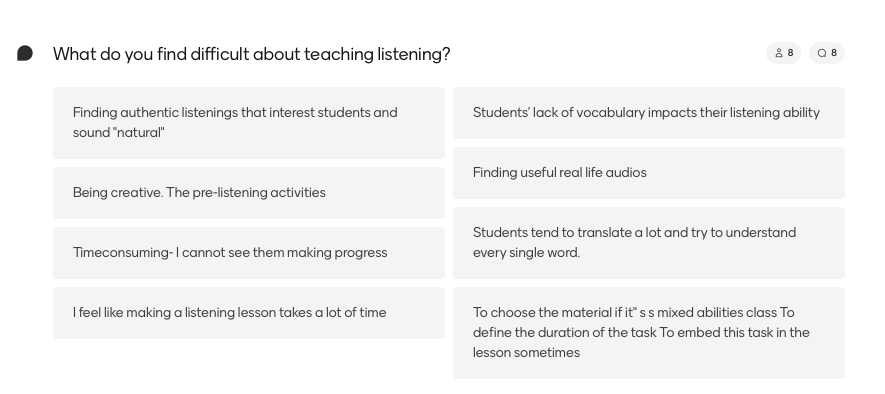

But first…I asked attendees in Madrid two questions: what their students find difficult about listening and what they find difficult about teaching listening. Here are their responses:

These ideas show what makes listening so difficult: speed, accents, distractions, concentration, unfamiliar vocabulary. When they’re tackling a reading text, our students have control: they can re-read, choose the speed they read, switch easily between questions and text. When listening, however, everything is controlled by the audio.

In these responses, we see that teachers struggle with the time-consuming nature of doing listening activities and finding ways of making the tasks meaningful by choosing more relevant texts.

I think listening is a challenging skill for the reasons summarised by Ekaterina Nemtchinova here: ‘Many teachers consider teaching listening challenging because it is not clear what specific skills are involved, what activities could lead to their improvement, and what constitutes comprehension. Students are also frustrated because there are no rules that one can memorize to become a good listener’ (2013: p.1).

I want to explore that comment about comprehension a little more, because the title of my talk (and this blog post) are directly related to this element. What does it mean to comprehend something? Nemtchinova (2013) talks about comprehension saying ‘Understanding a message does not mean remembering every single detail, so students’ inability to recall information does not always signal a lack of comprehension. Yet some exercises—namely, multiple-choice and very specific questions—test listeners’ memory skills rather than focusing on the listening process’ (p.12). I did a little experiment at the presentation where I gave six comprehension questions with multiple-choice answers and then read the attendees a short text to see how well they got on. Oh, this was all done in Welsh; a language that was not spoken by any of the attendees, but all of them got 100% on the task! When we design comprehension tasks we have to be very careful to check that we are not testing mechanical listening.

Course book recordings and authentic listening texts

Attendees mentioned the difficulty in finding real-life recordings. I suggested making our own. I asked about a dozen friends/ex-colleagues/contacts to make a short audio recording of themselves talking about everyday life; crucially, I asked people with a variety of native and non-native accents. I’ve now used these recordings with a number of groups for them to practise listening to real people talking about real things. That I know the speakers, adds interest and intrigue to the activity.

Another idea is to find good model speakers from the same language background as your students (sports stars, actors, musicians, etc.) giving interviews in English. Ivana Baquero is a great example for Spanish speakers, but the better known the speaker is to your students, the better the results.

A final way of finding and using real life listening texts (and be careful with permissions with this one) is using your students themselves to generate the audios. Have them record themselves talking about whatever the current theme of the class is: students could generate questions that they answer in a recording, or interview one another in pairs and record the result. This can double up as practice in extending spoken responses as well as generating interest in doing whatever listening activity you choose.

Transcripts

If you have ever heard me give a presentation, it’s more likely than not that I’ve talked about audio transcripts. They’re usually tucked away at the back of the book, in small print. Yet, they are a goldmine of language to be extracted.

The first stage is simply to have students check their answers by turning the listening activity into a reading activity.

Then, for answers students got right, they need to identify the clues that led them in the right direction. On the other hand, for wrong answers, students need to identify why they made the mistake and what the correct answer is (and why).

After that, what other language can be mined from the text? Are there unknown phrasal verbs or colloquial expressions that would be useful for your students.

Finally, have your students write some questions of the type that you are practising based on the transcript and swap them with a partner for another listening.

Possible Activities (that aren’t multiple choice)

- Rather than giving students a list of questions with four possible answers, teach them to make brief notes on what they hear. They could have the questions and just bullet point what information they get from the track that answers the question. Another approach is for students to draw a table with common elements to listen for from a number of speakers. Later you could distribute the multiple-choice element for them to consider alongside their notes.

- Prediction is key with listening. There is so much cognitive load impacting students when they are listening, having an idea of what they expect to hear is essential. Think about the notes-completion task in Cambridge; often it’s possible to have a pretty good idea about one or two of the answers before the track even begins. This is often the case with authentic listening…we can have a pretty good of what someone is going to say based on what they have just said. How much pure listening do we do when we are working in a language we speak fluently versus how much prediction do we do?!

- Listening just for specific language is helpful for students to find their way into a text. At lower levels, this might be a simple task for students to write down all of the fruits, sports, etc. that they hear. At intermediate levels, we might ask students to identify the discourse markers first and then listen again to hear what was said (quite useful for Cambridge B1 Part 1). At more advanced levels, we might ask students to listen for contractions and connected speech, again, before giving them a specific task to do.

- If your more advanced learners are familiar with the IPA, a useful task is for them to transcribe short sections of audio. Students can then compare transcriptions, discuss differences and difficulties and begin to think on a different level about the listening they are doing.

And finally, Real Life Listening

Listening in an exam is passive; listening in the real world, however, is active. We might be teaching an exam prep class, but at some point our students are going to go out into the world and listen in English. This means that I think we need to teach our students how to listen actively:

- Body language and eye contact;

- Phatic language that show engagement in the dialogue;

- Communication repair strategies;

- Note-taking.

Over to you!

I ended my presentation by opening up the floor to questions, comments and suggestions and I’ll do the same here. If you have a great listening practice idea or a favourite way to use authentic listening texts, add a comment below.